A Revolutionary Point of Gathering: The Impact of Neighborhood Planning Councils

by V.V. Janney

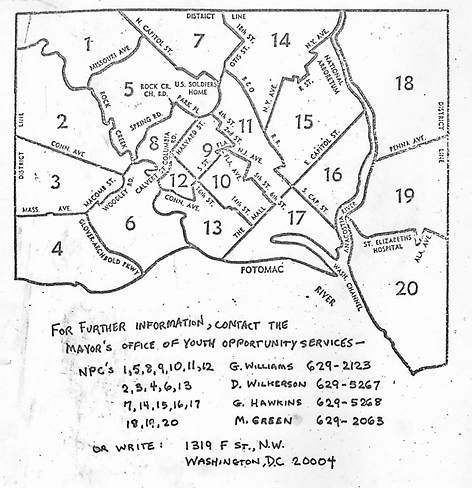

Neighborhood Planning Councils (NPCs) were a form of youth engagement and development that began in Washington DC in the late 1960s. The idea was born in 1966 “out of a need for citizen involvement in planning” (Sarmiento 2024). In 1966 many government organizations and young people came together for a conference to assess the problems with the current summer youth enrichment programs. The main complaint from residents across DC neighborhoods was not being involved in the development of programs. After this conference, the city was divided into 20 neighborhood planning areas. Each Ward in DC had at least two NPCs with elected board members (half youth and half adult) from within the boundaries of the NPC (Washington, D.C., Legislature 1968). Below is the map, depicting the boundaries. The structure of an NPC was meant to ensure that people, specifically the young people themselves, from each area in the city were represented through a democratic process.

Map of the NPC borders in accordance with the 1968 law. Source: Tony Sarmiento

At their core, NPCs were meant to provide a creative outlet where young people had power and agency in their communities. Each NPC gave young people in the area a paid job revolving around truly creative projects and endeavors. Young people, specifically at NPC #2 and #3, worked on archeological digs, dance societies, and modern music programs (Shwartz 2016). Young people in North East DC participated in a courtesy patrol where the youth would accompany seniors on walks in the neighborhood to facilitate a feeling of safety (Sarmiento 2024). Across the NPCs, many young people worked on neighborhood histories, specifically in Chinatown and the Shaw neighborhood (Sarmiento 2024). The local programming and project grants were performed by the NPC board, meaning the youth helped plan and decide what they worked on (Washington, D.C., Legislature 1968).

The law implementing NPCs claimed to reorganize the current patterns of youth organizing and provide a solid groundwork for economic development (Washington, D.C., Legislature 1968). The law described an NPC’s structure as “adult and youth participation in the development, implementation, and evaluation of programs for children and youth” (Washington, D.C., Legislature 1968). The reorganizing of the current patterns in youth organizing ensured that young people were part of their government structure and program development.

Emily Schwartz, director of Community for Careers at NPC #2, described it as “…a movement feel. Members fed off each other’s enthusiasm and commitment” (Schwartz 2016). The structure and implementation of NPCs “brought people together in a beautiful way” (Schwartz 2016). They were built to ensure kids had power in their community and shaped the services that were being provided to them. As a member of NPC #18 wrote in 1971, “the process in this case becomes” (Hawkins 1971). With this structure in place, young people made powerful impacts on their communities.

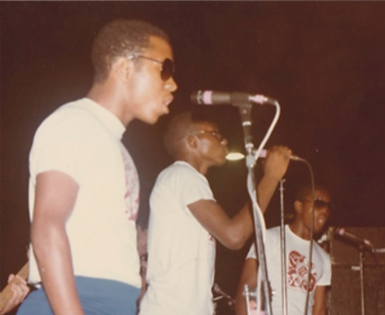

Specifically, NPC #3 played an integral role in the Fort Reno Concert series, which still exists today. Teenagers in DC punk bands worked for NPC #3 creating flyers for upcoming shows at Fort Reno (Schwartz 2016). They practiced in the backroom for their concerts on the Fort Reno stage (Schwartz 2016). NPC #3 gave these students an opportunity to delve into a creative, connective experience with each other and their community. People who worked at NPC #3 and participated in Fort Reno shows described to Ryan Little in the Washington City Paper the time as “eternal—not because of its grandeur, but because it was a nice hang” (As told to Little 2011). Today, looking out in the crowds at a Fort Reno show, it is filled with multiple generations. People who grew up attending or playing in Fort Reno concerts now bring their kids to these shows. Ian Mackaye, the singer in DC punk band Fugazi, states, “What’s revolutionary is it’s a point of gathering, and it doesn’t make a difference who’s playing” (As told to Little 2011). A point of gathering is revolutionary—a gathering shaped in part through the NPC #3.

LEFT: The Dynamic Ratz playing at a Fort Reno show in 1983. Source: Emily Shwartz.

RIGHT: Fugazi show in July 2002. Source: Unknown, Courtesy of the Fugazi Live Series.

NPCs did not go without criticism. In an editorial published in 1971 by Curbstone, a newspaper for DC youth news, an author explored the productiveness of the youth programs, specifically for Black young people in the city. Titled, “A Question of Viewpoints,” the author argued that some people feel the programs are useless if they are only “keeping kids off the street” (Finucane 1971). Along these lines, there were issues with the allocation of funding and debates about where it should go. After talking to Tony Sarmiento, who worked closely with NPC #2 and the Mayor's Office on Youth Opportunity Services, it is clear that funding was central to the success of NPCs.

In Sarmiento’s words, the money was not used as a “token,” it provided concrete sources of funding for beautiful projects within the community such as the Fort Reno Concert series or the numerous neighborhood history projects (Sarmiento 2024). NPC #3, at today's price level, had $800,000 in funding that went towards paying teenagers to put on punk shows and fostering a community asset and gathering place (Sarmiento 2024). NPC #18, which had a large number of poor children and young people in its borders, had four million dollars (Sarmiento 2024). Sarmiento explained that the amount of funding made it especially important to ensure that the money was going towards effective and loving projects, which did spark some controversy. However, with that amount of funding for a single NPC and with a board of 50% young people, there was a real capacity for meaningful and impactful work that did not keep kids off the streets, but helped make the streets beautiful, loving, and safe. The young people that participated in NPCs wanted to protect and uphold the participatory values of NPCs and ensure that funding went to important and valuable projects.

Sarmiento made the connection of NPCs to a similar program in DC: Advisory Neighborhood Councils (ANCs). ANCs were created so hyperlocal concerns were accounted for in the DC government structure and is composed of a board of residents in the neighborhood. However, ANCs have significantly less funding and are purely advisory. Therefore, ANCs real power lies in stopping things from happening instead of fostering meaningful projects and work. For example, in 1975 an ANC imposed a curfew on the young people in the community. Jean Hoffman, a youth member of the NPC in this neighborhood, said in a testimony in response to the curfew, “the opportunity for youth to ‘plan, staff, implement and evaluate community based youth programs’ is unique and should not be lost in the initial rush of ANC power or delegated to an institutionalized citizens association” (Hoffman 1975). The young people involved in NPCs loved being a part of this program and worked hard to uphold their voices and values.

However, funding for NPCs eventually dried up and each one was disbanded around the late 1980s (Schwartz 2016). Today, the location of NPC #3 sits abandoned on the corner of Fort Reno covered in graffiti. Funding for youth development shifted away from the NPC structure and ANCs overtook the primary form of citizen involvement. Today, DC invests millions of dollars in youth development and engagement primarily in the form of grants. DC invested $22 million alone in community organizations that provide after school programs to “more than 15,000 DC youth” (Executive Office of the Mayor 2024). Just recently, 11 non-profits were awarded nine hundred thousand dollars to prevent youth violence, including the beloved organization Horton’s Kids (Hamburg 2024). In response to a “public emergency” to the large increase in youth violence in the city funding for youth organizing increased and was redistributed to local organizations (Executive Office of the Mayor 2024).

A 2023 report from Fair Chance detailed current issues in DC’s youth organizing by facilitating different discussions and panels with DC Public School students. Through these discussions they found that young people need more safe, accepting, and open environments where they can express themselves “without judgment” and “decide for themselves what they want to do” (Van der Veer et al. 2023). For their final finding, they emphasized the importance of embedding young peoples’ voices in organizing and providing opportunities to “participate at the Board level as well as organizational leadership sessions, and events” (Van der Veer et al. 2023). These characteristics sound familiar to the 1966 conference that laid the groundwork for NPCs and the 1968 law outlining NPC’s structure.

Fort Reno Stage in 1997, with the NPCs 5 and 6 spray painted on it. Source: Ian Mackaye

The opportunity NPCs gave young people resulted in a government initiative to be proudly spray painted on a stage (shown above) that still serves the community today. A youth engagement program that centers young people as leaders of their own program and community will be beneficial for both the individual kids and the neighborhood. NPCs were powerful in the 70s and would be powerful now, if we let them.

--

Bibliography

Executive Office of the Mayor. "Mayor Bowser Awards $22 Million to Community Organizations Providing Out-of-School Time Programming to More Than 15,000 District Youth." News release. August 30, 2023. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://mayor.dc.gov/release/Mayor-bowser-awards-22-million-community-organizations-providing-out-school-time-programming.

Executive Office of the Mayor. "Mayor Bowser Issues Public Emergency to Give District New Tools for Responding to Opioid Crisis and Increase in Youth Violence." News release. November 13, 2023. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://mayor.dc.gov/release/Mayor-bowser-issues-public-emergency-give-district-new-tools-responding-opioid-crisis-and.

Hamburg, Daniel. Daniel Hamburg to DC News Now newsgroup, "11 DC Non-Profits Awarded Nearly $900K toPrevent Youth Violence," March 21, 2024. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://www.dcnewsnow.com/news/local-news/washington-dc/11-dc-non-profits-awarded-nearly-900k-to-prevent-youth-violence/.

Hearings Before the Committee of Education and Youth Affairs, 1975 Leg. (D.C. Mar. 27, 1975) (statement of Jean Hoffman).

Little, As told to Ryan. "[Your Band] Played Here." Washington City Paper. Last modified August 5, 2011. Accessed March 23, 2024. https://washingtoncitypaper.com/article/217705/an-oral-history-of-fort-reno/.

Finucane, Matt. "A Question of Viewpoints." Curbstone: DC Youth News (Washington, DC), July 21, 1971.

Sarmiento, Tony. Interview by Vera Janney. Washington, DC. March 28, 2024.

Swartz, Emily. "Chevy Chase Desegregates and the Neighborhood Organizes Youth Services: Nephew, Aunt Tell of Experience." Interview by Timothy Hannapel. In Historic Chevy Chase.

Van der Veer, Gretchen, Daon McLarin Johnson, and Valarie Ashley. Youth at the Center: Insights from Youth for Youth Development Professionals. Washington, DC: Fair Chance, 2023.

Washington, D.C., Legislature. Neighborhood Planning Councils. D.C. Reg., vol. 1968, 1968. Act no.2–1503.01.